It has been a joy and a professional privilege to work with colleagues editing books for teachers. With Fred Waage and Laird Christensen, I co-edited Teaching North American Environmental Literature (2008) and, with Sean Meehan, Approaches to Teaching the Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (2018). Both volumes appeared in the Modern Language Association’s Options for Teaching series. I am now beginning work on a volume for the MLA series Approaches to Teaching World Literature: “Approaches to Teaching the Works of William Carlos Williams.”

The collection will offer secondary and post-secondary teachers, graduate students, and independent scholars, a resource for teaching a poet whose work is widely regarded as among the most innovative and influential of the twentieth century. This is the perfect time for such a volume: Williams’s commitment to the poor and the working class as well as his own multicultural and multilingual background, alongside his democratic insistence on ordinary language and experience as poetic, speak to our current time, just as his poetic innovations have spoken and remained relevant to poets of various schools who have claimed Williams as their main influence.

Although Williams is among the most recognizable twentieth-century American poets, he is often the most difficult to teach. The challenge of teaching Williams is not that his poems are difficult or inaccessible. Rather most readers in secondary school English, undergraduate surveys of twentieth-century American literature, literary Modernism, or American poetry and poetics come to know Williams as the author of a few short lyrics––among them “The Red Wheelbarrow,” the “plums poem,” “By the Road to the Contagious Hospital,” and “This is Just to Say.” The volume will feature materials and courses for introducing these well-known works alongside the less-known but widely-influential lyric poems, the early experimental work, including Kora in Hell and Spring and All, the book-length poem Paterson, the translations of Spanish and Latin American verse, and Williams’s wide-ranging and provocative fiction and nonfiction.

The “Materials” section will introduce Williams’s writing and related resources. Our introduction will introduce the standard editions published by New Directions Press: The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams: Volume I, 1909–1939 (1986); The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams: Volume II, 1939–1962 (1988); Paterson (1992); and By Word of Mouth: Poems from the Spanish, 1916–1959 (2011). We will survey the fiction, short stories, and experimental writing, including the works collected in The Selected Essays (1954) and Imaginations (1970), as well as the book-length study of American history and culture In the American Grain (1925). A biographical sketch will situate Williams’s creative work in relation to his multiethnic background as well as his life-long medical practice in Rutherford, New Jersey. We will provide a pedagogically-oriented overview of the secondary commentary as well, including the extant biographical resources, bibliographies of secondary materials, and major studies of Williams’s modern poetry and poetics.

We will also offer teachers materials that document the resurgence of Williams’s presence in the modern poetic tradition around the world––from Julio Marzan’s The Spanish American Roots of William Carlos Williams (1994) to Jonathan Cohen’s collection of Williams’s translations in By Word of Mouth: Poems from the Spanish, 1916–1959 (2011), as well as scholarship in both the “Materials” and “Approaches” sections, more broadly, to elaborate Williams’s Latinx heritage, his indebtedness to the traditions of Peninsular and Colonial Spanish literature, and current literary criticism and theory on the relations of culture, power, and aesthetics in the Caribbean that engage with Williams’s legacy. The “Approaches” section, moreover, will (re)situate Williams’s distinctive modernism around issues of linguistic, geographic, and cultural translation as well as creative writers. We will also compile the available and reliable web-based materials—including the recently completed open-access digital concordance to the poems in the Williams corpus.

The “Approaches” section will also introduce readers to the life and work of the small-town doctor who published more than forty books of poetry and prose and who irreversibly shaped the arc of poetry and poetics during the twentieth century. We plan to include essays on teaching Williams as an avant-garde writer in the early modernist period during and after World War 1 using Al Que Quire! (1917), Spring and All (1923), and The Wedge (1944). And we envision essays on the complex literary and cultural politics of Williams’s reception as a poet through the late 1950s and 1960s, and approaches to the work in the later period that encompasses the publication of Paterson (1946–1951), Collected Later Poems (1950), Collected Early Poems (1951), Make Light of It: Collected Stories (1950), the Autobiography (1951), Selected Essays (1954), The Desert Music (1954), Journey to Love (1955), and Pictures from Brueghel (1962).

Williams was a tireless supporter and mentor of younger poets, and teachers will find new ways to include in their courses on modernism his reviews and early essays on the writing of Gertrude Stein, Mina Loy, H.D., and Marianne Moore, and his promotion of the work of numerous individual poets, including Allen Ginsberg (writing the introduction to the City Lights edition of Howl); Muriel Rukeyser, a feminist poet affiliated with the Popular Left Front; and Amiri Baraka, who described Williams as the “common denominator” of the New American Poetry and the poet who had taught him “how to write in my own language—how to write the way I speak rather than the way I think a poem ought to be written.”

We will include an essay on Williams’s editorial and creative contributions to both prominent and peripheral little magazines (Others, Contact, Origin, Black Mountain Review, Yugen) and a teacher-oriented approach to his poetics in relation to the aesthetics of high-Modernism and the New Criticism. For with his college friend Ezra Pound, Williams provided a foundation for the “schools” of poetry Donald Allen identified in The New American Poetry (1960): Black Mountain, San Francisco Renaissance, Beat, and New York; and he collaborated with Louis Zukofsky to promote “Objectivist” poetics and the poems of Basil Bunting, George Oppen, Carl Rakowski, Charles Reznikoff, Kenneth Rexroth, Charles Olson, Robert Lowell, and Denise Levertov. One reason Williams remains a singular presence among modernist poets is his dedication to vernacular forms of expression in local environments and, more specifically, his poetic engagement with the working-class lives he encountered through his medical practice. The publication of Imaginations (New Directions 1970), moreover, provided creative inspiration for “Language Poetry,” (what Ron Silliman has called “third-phase objectivism”) that began in the 1930s and was reanimated by Silliman and other poets, such as Bob Perelman, Bob Grenier, and Charles Bernstein, as well as taken up by feminist experimental writers, including Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Alice Notley, Lyn Hejinian, and Rae Armantrout (a student of Levertov).

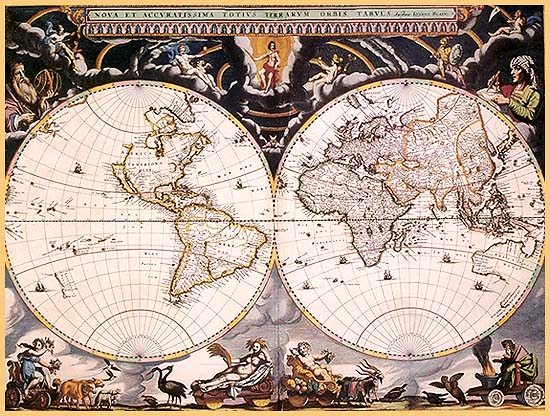

The “Approaches” section will include essays that address the ways that Williams was entangled in American history and identity, engaged with the inheritance of European literary and cultural traditions, and concerned with the transnational and multilingual dimensions of language and literature. To this end, we are committed to providing teachers access to approaches and materials for engaging with Williams’s preoccupation with cultural identity and the challenging questions associated with literary inheritance, including the patriarchal and heteronormative assumptions in his work, the cross-cultural complexities of his hemispheric interest in the literary and cultural history of the Americas, and his Puerto Rican heritage. (His mother, Helena Hoheb, was born in Mayaguez, Puerto Rico). An essay on Williams as a translator of Spanish and Latin American poets will provide teachers with resources for teaching Williams in relation to such poets as Cuba’s Eugenio Florit, Chile’s Pablo Neruda and Nicanor Parra, Ecuador’s Jorge Carrera Andrade, Costa Rica’s Eunice Odio, Nicaragua’s Ernesto Mejía Sánchez, Argentina’s Silvina Ocampo, Uruguay’s Álvaro Figueredo, Mexico’s Octavio Paz and Ali Chumacero, and the Puerto Rican Luis Palés Matos.

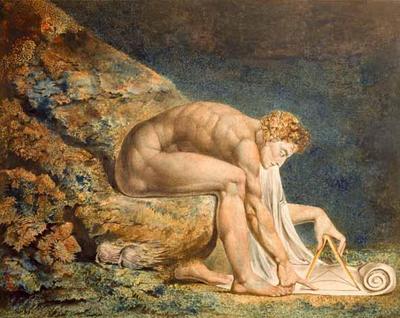

In addition to the poems, we will provide teachers with pedagogical approaches to teaching Williams as a prose writer: the short stories, novels, plays, autobiographical writing, and essays on poetry and the arts—including his contributions to the genre of the literary essay; the literary-historical method of book–length studyIn the American Grain (1925); the novels and short stories, such as A Voyage to Pagany (1928), White Mule (1937), and Life along the Passaic River (1938); and The Doctor Stories (1984).We will offer approaches to teaching the book-length poem Paterson, including in relation to urban planning and local environments; an essay on Williams and the visual arts, exploring his relationships with Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, Alfred Stieglitz, and Charles Sheeler; an essay that provides insight into working with the biographical materials; and an essay on studying Williams’s literary and cultural relations and legacies, for instance, his reflections on education in his essays and philosophical fragments written in the late 1920s, and published posthumously in 1974, The Embodiment of Knowledge. Finally, the volume will feature approaches to teaching Williams using tools from the Digital Humanities that use mapping technologies and hypertextual online annotations to collaborate with students in shared projects that use data processes and new media to re-investigate Williams’s work.

I am fortunate to be working with an amazing editorial team for the volume, talented collaborators and inspiring colleagues, who share my passion for teaching as well as writing about Williams. What is more, each of us teach and study Williams at institutions with different missions and students served, and our institutional and scholarly locations will strengthen the development of the volume. One of my co-editors is Daniel Burke, immediate past president of the William Carlos Williams Society, recently organized the biennial conference of the Society in Chicago with support from his home institution, Arrupe College of Loyola University Chicago, the Poetry Foundation, and the University of Chicago. The other co-editor, Elin Käck, who teaches at Sweden’s Linköping University, is currently Vice-President of the Society, who recently chaired an MLA session celebrating the centennial of Williams’s Spring and All, and who brings her perspective and scholarship on Williams and ideas of tradition and Europe in modernism and American poetry.

The MLA is currently inviting interested teachers and scholars to take a survey and to submit proposals for the new volume on teaching the works of William Carlos Williams. Survey responses and proposals are due 1 June.