Every detachment prepares a new detachment. Of course, prophecy becomes habitual and reaches all things. Having seen one thing that was firmament enter into the kingdom of growth, the conclusion is irresistible, there is no fixture in the Universe. Everything was moved, did spin, and will spin again. This changes once and for all his view of things. Hint of dialectic: Things appears as seeds of an immense future. Whilst the dull man seems to himself always to live in a finished world, the thinker always finds himself in the early stages; the world lies up to him in heaps and gathered materials;—materials of a structure that is yet to be built.

from “The Relation of Intellect to Natural Science” (1848)

Few men know how to take a walk. The qualifications of a professor are endurance, plain clothes, old shoes, an eye for nature, good humor, vast curiosity, good speech, good silence, and nothing too much. If a man tells me he has an intense love of nature, I know, of course, that he has none. Good observers have the manner of trees and animals, their patient good sense, and if they add words, ‘tis only when words are better than silence. But a loud singer, or story teller, or vain talker profanes the river and the forest, and is nothing like so good company as a dog.

from “Country Life” (1858)

Last week I received in the mail “The Best Read Naturalist”: Nature Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, edited by Michael Branch and Clinton Mohs. When I was asked to review the manuscript of this book for the University of Virginia Press, I was teaching the biologist E. O. Wilson’s The Meaning of Human Existence (2014). Reading Emerson and Wilson I was intrigued by the congruence between the questions both authors are asking. “Does humanity have a special place in the Universe? What is the meaning of our personal lives? Where are we going? Why?” These are Wilson’s questions, presented in the spirit of reasoning about what he calls “the relation between science and humanities.”

It strikes me that this is precisely the line of reasoning that Emerson enacted with his audiences in the lyceum. Branch and Mohs build on this connection between Emerson’s fascination with natural science and his humanistic exploration of our place in the world, arguing that Emerson “illuminates the importance of nineteenth-century natural science to the evolution of American ideas about the environment” (ix). For example, in one of the talks included in this anthology, “Humanity of Science” (1836), Emerson writes, “In a just history, what is the face of science? What lesson does it teach? What wisdom will a philosopher draw from its recent progress?” (140). This series of questions offers teachers and students access to Emerson’s engagement with the social and cultural history of natural science.

As it happens, about the same time I read the manuscript of “The Best Read Naturalist” a student showed up in one of my classes prepared to talk about an essay by Emerson. The student raised his hand. He then asked a question. “How do I begin to talk about the essay when I have highlighted every word in the opening paragraph?”

This is the same student who, in an essay I had asked him to write on his experiences with reading and writing in school, described his belief that the purpose of the academic essay “is to break the illusion of false knowledge.” He then pointed out, “of course essays are assigned so teachers can assess a student’s understanding, but they also allow students to assess their own understanding. For me,” he concluded, “the written word has become a way to audit my thoughts from a neutral point of view so that I may realize the flaws of my thought process.”

Then, a few weeks later, we read Emerson’s essay “Illusions” from The conduct of Life:

There are as many pillows of illusion as flakes in a snow-storm. We wake from one dream into another dream. The toys, to be sure, are various, and are graduated in refinement to the quality of the dupe. The intellectual man requires a fine bait; the sots are easily amused. But everybody is drugged with his own frenzy, and the pageant marches at all hours, with music and banner and badge.

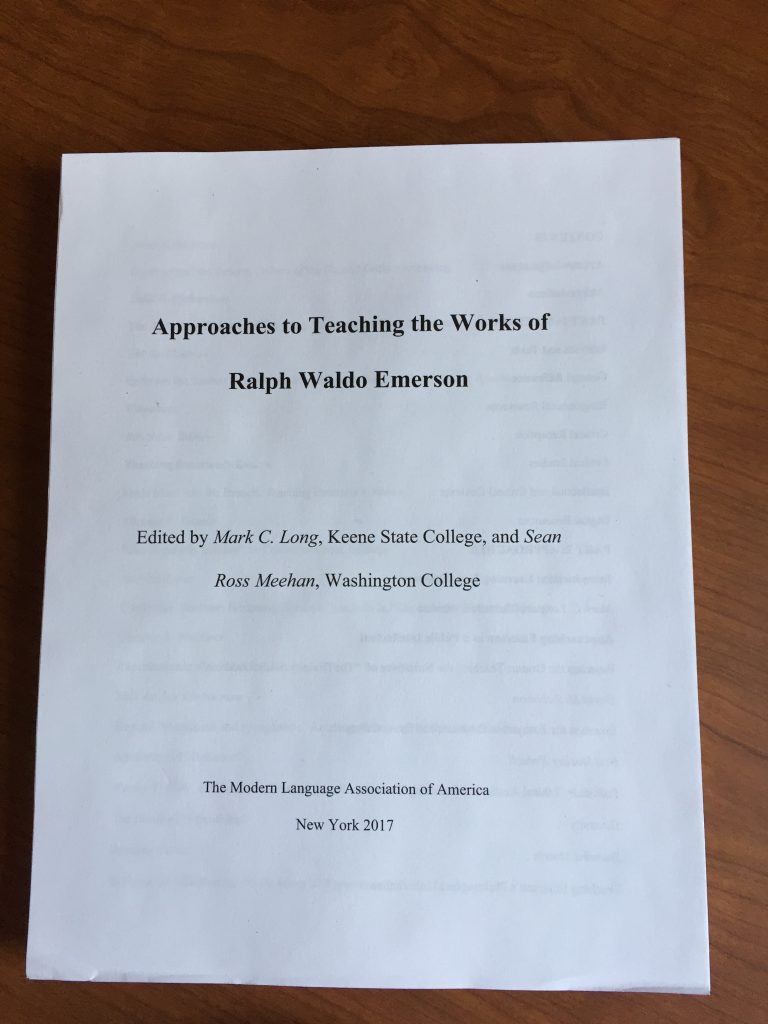

In the introduction to the book I recently co-edited with a colleague who teaches at Maryland’s Washington College, Sean Meehan, Approaches to Teaching the Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, we remind our readers that ever since F. O. Matthiessen made him a founding figure of the “American Renaissance,” Emerson has remained a staple of undergraduate surveys in American literature and seminars on the “Age of Emerson.” We go on to describe the wide-ranging global, not just national, presence of Emerson’s writing, across the Atlantic and around the world. Our collection of essays demonstrate the multiple ways contemporary students encounter Emerson’s works—in courses on Transcendentalism, Romanticism, environmental literature, literary theory and philosophy, rhetoric and composition, media studies, and genre courses in poetry and the essay, and in upper-level seminars.

Not only was Emerson a leading figure of American Transcendentalism and transatlantic Romanticism, prominent nineteenth-century poet and literary mentor. For he is one of America’s greatest essayist, and students frequently encounter his writing alongside Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Friedrich Nietzsche, William James, James Baldwin, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, Ralph Ellison, Mary Oliver, and Annie Dillard, to name a few. Emerson was also America’s first public intellectual. His addresses, essays, and poems were deeply engaged with the social and political issues of nineteenth-century America.

Teaching a seminar on Emerson, and working on our forthcoming book, I found myself spending more time with Emerson’s writing. Work had just been completed on the ten-volume scholarly edition of all of Emerson’s works published in his lifetime and under his supervision, The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. The culmination of a half-century of vigorous textual editing, I now had access to the full range of Emerson’s writing and thinking. The publication of this textual scholarship—beginning with The Early Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the sixteen volumes of The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, extending to The Complete Sermons, The Poetry Notebooks, The Topical Notebooks, the four-volume supplement to The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson and The Selected Letters, Emerson’s Antislavery Writings, The Later Lectures and Selected Lectures—reintroduced me to Emerson and to the ways that Emerson worked and thought through his ideas in the medium of writing.

Approaches to Teaching the Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson recognizes Emerson’s continuing presence in the curriculum and offers instructors a pedagogical resource to guide and inspire the teaching of Emerson. The Table of Contents for the book that will be published later this year offers a preview of the contexts and the range of scholars engaged with Emerson’s work.

PART 1: MATERIALS

Editions and Texts

General Reference

Biographical Resources

Critical Reception

Critical Studies

Intellectual and Critical Contexts

Digital Resources

PART 2: APPROACHES

Introduction: Learning from Emerson Mark C. Long and Sean Ross Meehan

Approaching Emerson as a Public Intellectual

Emerson the Orator: Teaching the Narratives of “The Divinity School Address” David M. Robinson

Emerson the Essayist in the American Essay Canon Ned Stuckey-French

Politically Ethical Aesthetics: Teaching Emerson’s Poetry in the Context of U.S. Diversity Saundra Morris

Teaching Emerson’s Philosophical Inheritance Susan L. Dunston

Emerson and the Reform Culture of the Second Great Awakening Todd H. Richardson

The Turbulent Embrace of Thinking: Teaching Emerson the Educator Martin Bickman

Emerson the Author: Introducing the Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson into the Classroom Ronald A. Bosco

Teaching Emerson’s Essays

Once More into the Breach: Teaching Emerson’s Nature Michael P. Branch

“The American Scholar” as Commencement Address Andrew Kopec

The Divine Sublime: Educating Spiritual Teachers in “The Divinity School Address” Corinne E. Blackmer

Experimenting with “Circles” Nels Anchor Christensen

Beyond “mendicant and sycophantic” Reading: Teaching the Seminar “Studies in American Self-Reliance” Wesley T. Mott

The Ideals of “Friendship” Jennifer Gurley

In Praise of Affirmation: On Emerson’s “Experience” Branka Arsić

Teaching Emerson’s Other Works

Emerson in the Nineteenth-Century Poetry Course Christoph Irmscher

Teaching Emerson’s Antislavery Writings Len Gougeon

Approaching the Practical Emerson through the Sermons and the Early Lectures Carolyn Maibor

Emerson, Gender, and the Journals Jean Ferguson Carr

A Natural History of Intellect? Emerson’s Scientific Methods in the Later Lectures Meredith Farmer

Emerson Across the Curriculum

“These Flames and Generosities of the Heart”: Emerson in the Poetry Workshop Dan Beachy-Quick

Between the Disciplines and Beyond the Institution: Emerson’s Environmental Relevance T.S. McMillin

Emerson in Media Studies and Journalism David O. Dowling

Emerson and the Digital Humanities Amy Earhart

Emerson Around the World

Emerson’s Transatlantic Networks Leslie Elizabeth Eckel

Translating the Latin American Emerson Anne Fountain

Emerson and Nietzsche Herwig Friedl

Emerson in the East: Perennial Philosophy as Humanistic Inquiry John Michael Corrigan