Experiments often begin with “what if” questions. As I compose this post in the fall of 2020 one of the questions emerging at Keene State College is whether we will be able to support a portfolio platform to promote college-wide learning. What we mean by “college-wide learning” is less clear; and the connections we hope to make possible in our community of teaching and learning keep running up against the persistent inertia of institutional life.

We want our students to make connections across their experiences both in and outside the classroom. We want faculty and staff and students to work together to build learning pathways, or a network, that will integrate their learning as well as connect their college experiences to the first stages of their life and career beyond school. So far so good.

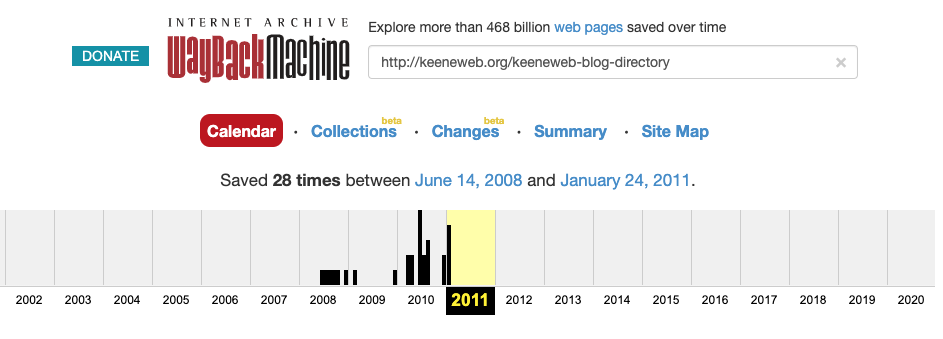

For some of us these aspirations are familiar. Some time ago, back in 2007 to be a bit more precise, a similar “what if?” question emerged : “What if the faculty and staff of Keene State College were given a place to blog?” The Wayback Machine at the Internet Archive offers a glimpse of that dusty virtual page in the vast archive of the web where that fabulous question lives on:

The experiment was a publishing platform. Our in-house instructional designer Mike Caulfield explained in a blog post Starlings in the Slipstream, would help us develop more meaningful communications and connections at the College. Mike connected the project to Jim Groom at the University of Mary Washington, who is another protagonist in the history of this question: for he had helped to design a platform to facilitate communications among faculty, staff, and students at UMW that would evolve into something more, what Jim called “networked learning.”

Back at Keene State College, Mike (and Jenny Darrow, his colleague in the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning) made possible some creative work using a Word Press multi-user blogging system with the option of building in RSS feeds for content. A few of us had already set up professional web pages on our own. (My forays in building a digital presence on the web began a couple of years after coming to the College, in 2000, with the assistance of a digital consultant, Maria Erb.) But a wider network began to become visible and by 2011 the Keeneweb Blog Directory listed over 200 active sites––faculty pages, teaching and research projects, and digital hubs for institutional initiatives. But the Internet Archive also shows that the network was active from 2008 to 2011.

In an early presentation to the campus community, a former colleague who I worked with in the first-year writing program, Tracy Mendham, pulled together a slide set and talk, “Pathway to Pedagogy,” in which she advocated for networked learning. Tracy was a trailblazer who taught a section of essay writing with the title “A Blog of One’s Own” in which her students found themselves writing on a blog. At the end of her presentation, she offered some advice that included two points that have guided many of us since:

- Stop worrying and learn to love the Web

- Make teaching and learning an experience for yourself as well as your students

The first piece of advice is an artifact in a discourse of which we were a part, a reminder of where we were––that is, worrying about the web. The second piece of advice is what I might want to describe as a threshold concept. For while the Wayback timeline represents the demise of a brilliant idea to support connected teaching and learning at Keene State College, it is also the case that a number of people have been thinking and making connections in new ways ever since. In fact, with the dedication and hard work of Jenny Darrow––one through line in this story––and my colleague in Biology, the open education superhero Karen Cangialosi––we are no longer worried about the web. We are instead working alongside faculty and students exploring the experience of teaching a learning at KSCopen.

My own professional work was irrevocably transformed. At the time a department chair, I began building things: a site to facilitate faculty exchange and make visible the extraordinary work of my colleagues; a web site for the English department; an English department course and syllabus archive; and a site for our Thinking and Writing faculty. Too, I found myself blogging and discovering the generative process of representing my professional work. My goal was to make visible the work of a college English professor. My working assumption was that a more visible story of a professor and students at work might offer reasons for people to value the intellectual work of teachers and students in public higher education.

Making Connections

But the most lasting and transformative impact of this moment at Keene State College was in the learning experience of my students. Tracy’s pedagogical insights into what she called at the time “social computing as means of facilitating academic discourse and developing writing skills” opened my mind. I could then fully appreciate what a colleague of mine was doing with his students at Washington College. Sean’s Comp| Post site was another node in a developing idea.

The idea, I can now see, was the network. My project exploration a kind of portolano chart with coordinates and sailing directions for thinking about teaching and learning.

That is, I had no mappa mundi with which to navigate the parts and the whole. And so I filled in my chart in medias res, learning by going where I had to go: I was learning to navigate open source software, for me Word Press, in an effort to integrate the pieces of my professional and personal life; and, most importantly, my chart began to trace new vectors as my students set up blogs and begin writing and making new connections with me, what they were learning, and their readers.

The idea of a portfolio of artifacts is familiar to those of us trained in the teaching of writing. And I had been using them since I began teaching in graduate school. Student course blogs, though, presented new opportunities to make the idea of an audience for writing, to take one example, less an abstract idea and more a real, lived experience of connecting with readers by writing on the open web. The public portfolio, moreover, led to students making connections across their courses and learning experiences beyond the classroom. Some students built sites that were repurposed for a job search or for projects beyond graduation.

But first and foremost, I was experiencing students learning more about writing, and themselves as writers, by using these tools. The other pedagogical possibilities of digital portfolios were showing up in metacognitive and experiential activities that decades of research has shown to be positively associated with genuine learning. However, what I also came to realize is that if we are going to ask students to engage in metacognitive work then it would make a lot of sense for teachers to model the very learning process that we know can make a difference.

So I started writing with my students. I began building my own portfolio across a semester (and across courses and teaching experiences) to make visible my growth and learning as a teacher. In one instance, I found myself writing a post in a class with students, Houses and Chairs, in which I say that writing on the web

“is different than writing for the web. When you graduate from college you will be writing more for the web. Why might this matter? The musicologist and digital media specialist Kris Schaffer proposes the following answer to the question:

Think about it this way. If I’m the first person to take a primary source, transcribe (or translate) it, and annotate it with hyperlinks, and my public, digital writing gains traction, it will fast become the go-to source at the top of the search results. My hyperlinks and commentary will become the portal to the resources that people engage to gain context, background, and nuance. It’s a tremendous responsibility, but also a tremendous opportunity, to connect my skills as an academic and a humanist to the issues of the day, in an attempt to bring nuance and truth to the public consciousness.

The essay I am quoting from here is written for students with a particular end in mind: I am (re)introducing them to the hyperlink. At the same time, my intent is to build out an argument about reclaiming the web as a network––enacting the very thing I am writing about. The post is an example of what more and more people have learned recently to call asynchronous pedagogy, or what I have learned to call on my teaching blogs “Teacher Talk.” Perhaps I will write a bit more about this dimension of my pedagogical approach to teaching reading and writing in the coming weeks. For now, though, if anyone is interested, the terminal moraine of these reflections and connections is right here, where you are right now, at The Far Field.

On Rediscovering the Network

What if we really did want our students to make connections across their experiences both in and outside the classroom? What if we really wanted faculty and staff and students to work together to build learning pathways, or a network, to integrate learning as well as to guide students as they connect their college experiences to stages of life or careers outside of school?

One place to start would be with the metaphorical structure of our thinking. Of course networked learning, and the web as a network, has deeper roots. The metaphor of Indra’s Jeweled Net, which appears in the Atharva Veda and is used by the Buddhist Tu- Shun (557-640 B.C.E.) to envision a vast net that includes jewels at each meeting point that represent individual life forms (atoms, cells, units of consciousness) that are interconnected so that a change in one is reflected in all the others. The metaphor has been used, more recently, to describe the complex interconnected networks formed by relationships between objects in a system, in computation, ecological thinking, and in accounts of social networks.

What I am wondering about here is whether this ancient surmise is one antidote to the modern pathology of thinking predicated on individual parts that fuels the individualistic and atomistic patterns of behavior that make it so very difficult to imagine ways to change the conditions of teaching and learning for the better. It is the manner of thinking and being in a system composed of parts––”departments,” “divisions,” “schools,” an so on––that just can’t seem to get around themselves when it is time to move. Most useful, then, at the moment, might be to pursue the provocative question, “what if?”

The question is, once again, the opportunities: how do we hold ourselves accountable to the space of minds thinking together before we develop plans within and beyond the constraints of the established systems of which we are a part?

Featured photo credit: John Dittli