“Knowing that nothing need be done, is where we begin to move from”

-Gary Snyder, “Four Changes,” Turtle Island (1974)

How do we address the social needs and demands of an economy, the natural constraints of ecology and the political imperatives of democracy? How do we think about the environment in historical, political, historical, sociological, economic, technological, and moral terms? And how do we reconcile the democratic freedoms at home with the imperialism abroad that feeds the greed for resources to feed our insatiable consumer economy? These complicated questions—at the center of the social movement (and discourse) we have come to call environmentalism—have motivated a range of writers whose cultural work begins with the paradox that the scientific, industrial and technological advances of the modern world have inexorably created an ecological catastrophe of massive proportions.

This semester I’m teaching a course in American and Environmental Studies that takes up these questions. Our focus is

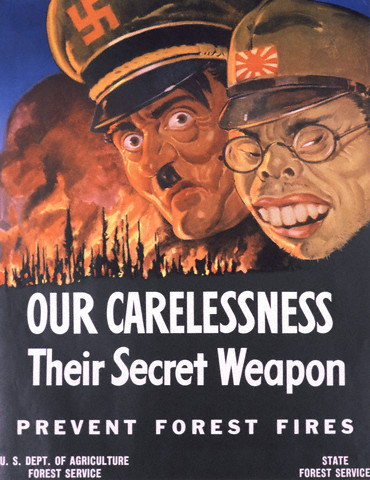

environmental writing and its relationship to the discourse of environmentalism. I’m interested in the ethical claims of environmentalism as a framework for considering how writers (and writer-activists) seek to foster reflection and transformation of personal assumptions and attitudes, beliefs and behavior. My course, “Writing in an Endangered World,” is an interdisciplinary course and therefore designed to address program outcomes in Environmental Studies (critical thinking and problem solving skills, communication skills, skills associated with moral and character development, an understanding of the ethical implications of environmental issues) as well as in American Studies (understanding historical and contemporary American cultures, responding resourcefully to texts, integrating forms of scholarship from more than one discipline, and the ability to write an effective documented essay that includes a thesis that integrates interdisciplinary approaches). To these ends, the course makes visible the assumptions, frameworks, and methods of the disciplines that study natural and human history, the relationship between ecological and human systems, and the history and values of environmental engagement in North America during the 20th century. In addition to reading Ramachandra Guha, Environmentalism: A Global History, students are reading Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, Gary Snyder, Turtle Island, Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang, Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, Linda Hogan, Solar Storms, Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild: Essays, Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge and T. C. Boyle The Tortilla Curtain. The course has also have considered the cultural presence of environmental concern in visual images, advertising campaigns, popular music, as well as other forms of cultural discourse.

I’m primarily interested in students thinking about how environmental writers use language as a primary vehicle for exploring the human prospect in an age of environmental crisis. Wendell Berry’s essays in The Unsettling of America, for example, ask students to consider the commonplaces that make possible our thinking about environmental questions. Berry enumerates the faults and contradictions of a system—call it what you will, capitalist, exploitative, free-market or global economy. Indeed Carson, Snyder, and Abbey all work from these commonplace ways of thinking. What makes this writing worth reading is that it moves beyond the limits of the language we make available to ourselves to address the problems we are being asked to think about. Imaginative writing takes many forms—including the writing we include in the genres of nonfiction, fiction, poetry. The language of this writing—its arguments, demonstrations, anecdotes and stories—serve as a counterpoint to what Wendell Berry calls our failure to reason about moral questions. “Public discourse of all kinds,” he insists in The Unsettling of America, “now tends to pattern itself either upon the arts of advertisement and propaganda (that is, the arts of persuasion without argument, which leads to reasonless and even unconscious acquiescence) or upon the allegedly objective or value-free demonstrations of science” (230). Berry’s claim about moral ignorance in The Unsettling of America is a provocation: a reminder that we are at once inheritors of a culture as well as stewards of that culture, and that the current state of the world is ultimately our responsibility. What do the current practices of agriculture, he asks, say about us? My case in the course is that Berry is not interested in the thinking that reinforces the opposition between saints and sinners (we are all both, he points out) or righteously pointing to the shortcomings or faults of someone else or some system or another. He is interested in the ways that we might move beyond thinking that begins “with a set of predetermining ideas” toward thinking that begins with “particular places, people, needs and desires” (233). He elaborates on this idea in chapter two, where he points to the problems of more ambitious institutional solutions that narrow and simplify as they propose particular actions or objectives.

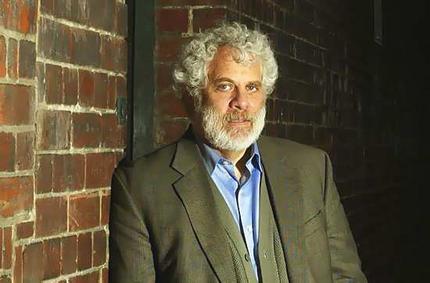

Our focus on writing about particular places, people, needs and desires was enriched by a class visit by the writer Mark

Kurlansky. Mark was on campus for one of the spring Keene is Reading program events. (We had selected his book Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World and he was in town to give a talk at the Colonial Theater on the long and complex history of the cod fishing and the depleted fishing stocks and the people’s lives who are linked to the great fisheries of the North Atlantic.) He talked with the students about the work of a writer; and, given the focus of the course, he addressed what it might mean to be a writer in an age of environmental concern. At one point he asked the students whether any of them had read Darwin. When he saw that none of the students had, he suggested that anyone interested in understanding contemporary environmental problems could do no better than to read and consider what Darwin makes visible in his work. The teacher of the course (me!) could not have asked for a more timely and apposite recommendation.