“If you have to ask that question, you wouldn’t understand the answer.”

––John McPhee, Coming into the Country

Field edges, sloped margins of fish ponds, straight irrigation trenches and tawny checkerboard fields of wheat, little groves of cultivated trees—all stitched with rows of leafy greens, backs of houses and industrial buildings as if set down in the orderly rows of greens that surround them, and out in the fields an electric scooter leaning against a fence and a crouched figure pulling weeds. Today we are driving north of the Yangtze River to the city of Yancheng.

Yesterday afternoon we arrived in Shanghai. It is a long haul from Toronto, Canada, and the first glimpse of China’s largest metropolis, a city of over twenty-four million people on the Yangtze River Delta, is difficult to describe. From the window seat a view of tight clusters of high-rise buildings built into networks of roads and open spaces that lead to other tight clusters of high-rise buildings stretching as far as the eyes can see. As the plane banks to position for landing, through surprisingly clear air, the afternoon light glitters on the surface of the Hangpu River.

We are coming into the country; and I sense that the world will no longer be the same. We will pay attention. We will see. We will change. Still, our slow descent onto the alluvial plain of the Yangtze River does not yet betray what we are experiencing:the most densely populated place on the planet. The Jiangnan—or the area south of the river—is now inhabited by the twenty-four million people of Shanghai as well as the other urban areas across the Yangtze River Delta region. The number of Chinese people in this small piece of the People’s Republic is 140 million.

Not only is the scale of the metropolis in China baffling but the clean and bustling and orderly Chinese city is incongruous. For we have come to thePeople’s Republic to gather with pastoral poets. While the pastoral has many versions, the tradition of values and poetics associated with this mode of thinking and poetic practice is the bridge we are walking between continents. WhatI find most exciting in this opportunity is to slip into the world of poets and poetry in a country with the longest continuous literary tradition in human history. At the same time, as I walk the streets of Shanghai, I remind myself of my plan to share with our hosts and audiences in Yancheng a pastoral impulse in our poetry and poetics that has yet to come to terms with the experience of living in the Anthropocene. Perhaps it is this place, after all, that signals most that we are living in a different world than we might have imagined.

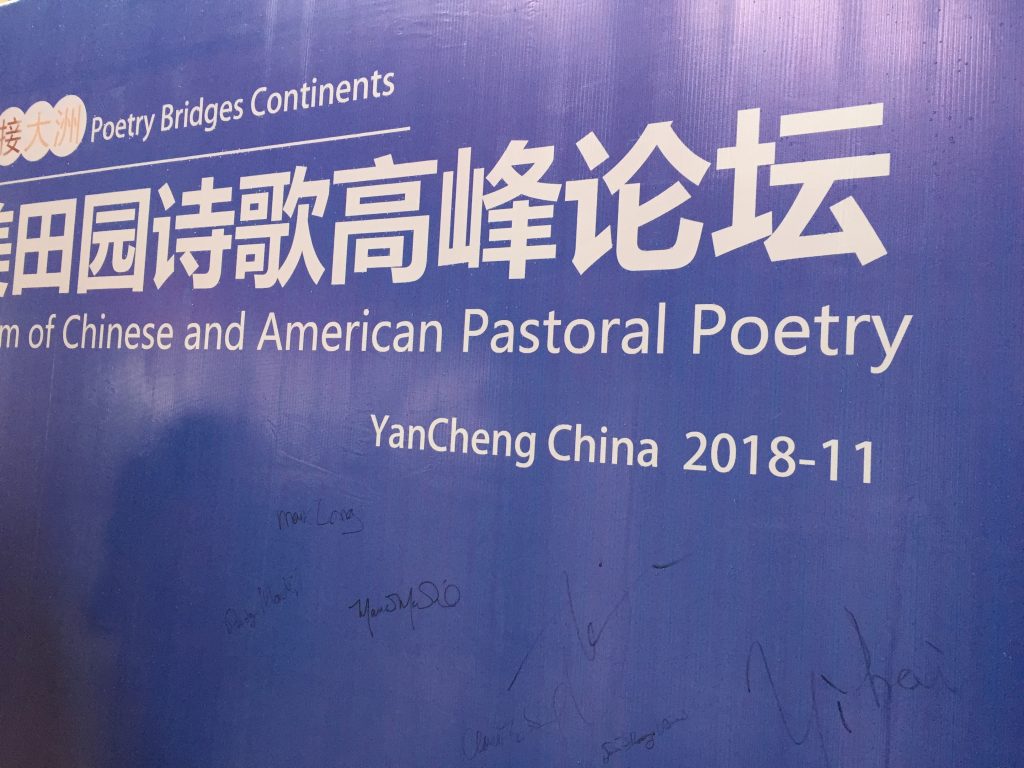

We are here in China as the featured guests at the Poetry Bridging Continents: From Walden to the Yellow Sea Symposium at Yancheng Teachers University. We are the poet Roger Martin, the visionary organizer of our trip, poets Susan O’Brien, Claire Golding, and Maura MacNeil, and my colleagues from Keene, archivist Rodney Obien and the dean of the Mason library, Celia Rabinowitz.

On the one hand, our trip to China is breaking new ground. We are here as protagonists in a sequel to the October 2017 colloquium “TheMagic of Monadnock: Poetry Bridging Continents” that brought Chen Yihai, from YanchengTeachers University, and Zi Chuan, poet and calligrapher, to the MonadnockRegion in New Hampshire. On the other hand, our travels are a continuation. We are here because of a cultural exchange that began thirty years ago with a collaboration between Michael True and a scholar and translator we are traveling with this week, Zhang Ziqing. We are here because of a 2006 anthology published in China, On American Pastoral Poetry that introduced the Monadnock Pastoral Poets, including Rodger Martin, Jim Beschta, Pat Fargnoli, Susan Roney-O’Brian, John Hodgen. And we are here because the cultural exchange continued with a 2011 visit by Beijing poet Bei Ta to New England that led to Roger’s 2012 sojourn to Hangzhou as part of the International Prominent Figure Celebration at West Lake. In 2015 Roger then returned to teach at Nanjing University and Shanghai University of International Business and Economics.

And so here we are. After settling in our Shanghai hotel on our evening of arrival, and enjoying our first taste of Chinese food, we walk the waterfront promenade, theBund, that is lined with colonial buildings. We join hundreds of others in the dark evening, drawn by the spectacle of the futuristic skyline of the Pudong district directly across the river from Shiliupu. Between making photographs of the lights and lining up to gather images of our first night in China, I can hear lines from a city poem in my head, from Gary Snyder’s Mountains and Rivers Without End:

Beautiful buildings we float in, we feed in,

Foam, steel, gray

Alive in the Sea of Information.

The Shanghai Tower soars six hundred and thirty meters above a river filled with illuminated boats cruising the dark waters and the Oriental Pearl TV Tower pokes out among dozens of square buildings plunging upwards into the dark sky. Each of the buildings are light screens flashing brilliant colors and patterns. At the top of the Tower, a cap of light streams race upwards into the darkness—as if to release into the sky.

Beautiful buildings for sure. When we return to the hotel everyone gathers their jet lag and heads to their rooms.Rodney and I decide to walk into the city night where we find a small bar and a cold beer to celebrate our first night in the People’s Republic of China–coming into the country.