Last month the Times reported that Andy Kessler died at the age of forty-eight. Kessler, as the obituaries page explained, brought skateboarding to New York City in the 1970s, and was a member of a community of skateboarders and graffiti artists named the Soul Artists of Zoo York.

It is fascinating to watch skateboarding organizing itself into the landscape of twentieth-century cultural history. The mythology in the Times, according to the writer of the obituary, is that New York skateboarding was neither the sport nor the cultural phenomenon as it was in California, “where scrappy, expert skateboarders like Jay Adams and Tony Alva created a style, ultimately a legend, that came to be called Dogtown.” Of course this is the Times, and it is New York, and the day after Kessler’s obituary appeared something else offered itself up: the acclaimed young fiction writer Bret Anthony Johnston—author of the internationally acclaimed Corpus Christi: Stories and the editor of Naming the World: And Other Exercises for the Creative Writer and a veteran urban skateboarder—published a brief essay titled “The End of Falling.”

By now you are probably wondering why a professor of English at Keene State College is writing about skateboarding. Well, it may have something to do with my years as a teenage rider in the 1970s, my sense of a larger cultural story about our generation, or simply species recognition: for here is an English professor (an award winning author, and current Briggs-Copeland Professor of Fiction position at Harvard, at that!) writing about skateboarding.

In “The End of Falling” Johnston admits that while he never knew Kessler, his life story was legendary among skaters in the city, a figure who pioneered a style of riding that Johnson calls a “gritty, dirty, and beautiful, the shadow-version of the breezy West Coast surf-style.” For this English professor, a one-time professional skateboarder, the image of a hip young professor of fiction at Harvard carving “gritty, dirty, and beautiful” turns on a sidewalk once walked by the likes of William James and W.E.B Du Bois sits well.

Kessler had a rough time, it seems. His story reminds me of a contemporary of mine in California, Jay Adams, whose unfortunate life path is featured in Stacy Peralta’s recent film Dog Town. Yes, drugs were a part of the skateboarding culture East and West, and it seems Kessler himself ended up hooked on heroin. He then turned a corner and led an effort to build a park for skateboarders and roller-bladers in Riverside Park—recruiting a group of disadvantaged youths to build it. The story resonates, at least for Johnston and perhaps his editor, as it falls into the broader contours of a story some of my generation appear to want to tell themselves. “Kessler’s great and lasting contribution to skateboarding,” Johnston intones, “was recognizing its transformative and transcendent qualities, the myriad ways in which a highly individualized endeavor invited, not precluded, community.”

Well, sure. I guess. Skateboarding is more than not a crime. More to the point, though, is that it is really hard to grow up, especially when the flimsy façade of privilege or youthful freedom breaks down and you find yourself struggling with the brutal facts of a flesh-and-blood life. My hunch is that the narrative Johnston is working with resonates for the over-forty crowd whose life revolves around scenarios predicated in the conceit that things are not what they used to be. And they are not, of course. Johnston deftly holds up the Kessler story as a counterpoint to the commodifaction of skateboarding and the skating culture, “the ubiquitous television presence, the department store displays of designer skater apparel, and the proliferation of free municipal skateparks around the country.” All this is rather dispiriting for a so-called breezy guy from California. But I can’t help but wonder about the cultural nostalgia that animates these kinds of stories. “For most of Kessler’s life,” Johnston goes on to say, “years of which were mired in violence and addiction and the existential angst that torments many a non-conformist, skateboarding wasn’t merely a sport or pastime or even the artistic expression of his soul. It was the path to his soul’s salvation.”

Johnston is a good enough writer to know that this kind of language is a stretch. So he excuses himself on his way to an almost passionate defense of skateboarding against those who still think of it as, well, criminal. “For all of their perceived destructiveness,” he writes, “for all of their purported unthinking and lawless mischief, skateboarders are a creative and compassionate breed. Often, especially when Kessler was nurturing what would become the East Coast scene, the kids who gravitated toward skateboarding were misfits and malcontents, the shy outcasts who’d been intimidated and sullied by the complex pressures of social interaction. Skateboarding gave them an identity and voice, and Kessler, by example, gave them the confidence to declare themselves to society.” Johnston here, appealing to his audience, rhetorician at large.

For me all of this is mildly reassuring. In northern San Diego, the California skate scene, as I experienced it in the 60s and 70s, was a natural extension of surfing—a way of biding time when the surf was not up. It was also a business, and a few found themselves with a lot of money. Still, the convening of young boys (and a few girls) seeking refuge from the complications and confusions of a post-60s culture was fueled by a deep sense of purpose—though I’m pretty sure none of us really knew what that purpose was. There was a powerful sense of freedom as we navigated our young lives in a slippery, drug- infested counterculture that in retrospect seems far less glamorous or important than people seem to want it to be. It was important as a relatively non-violent and mostly affirming path through adolescence and we tried to find a way to becoming adults.

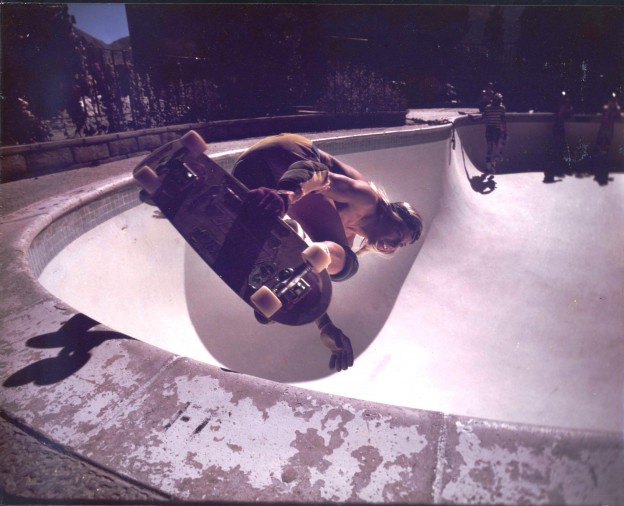

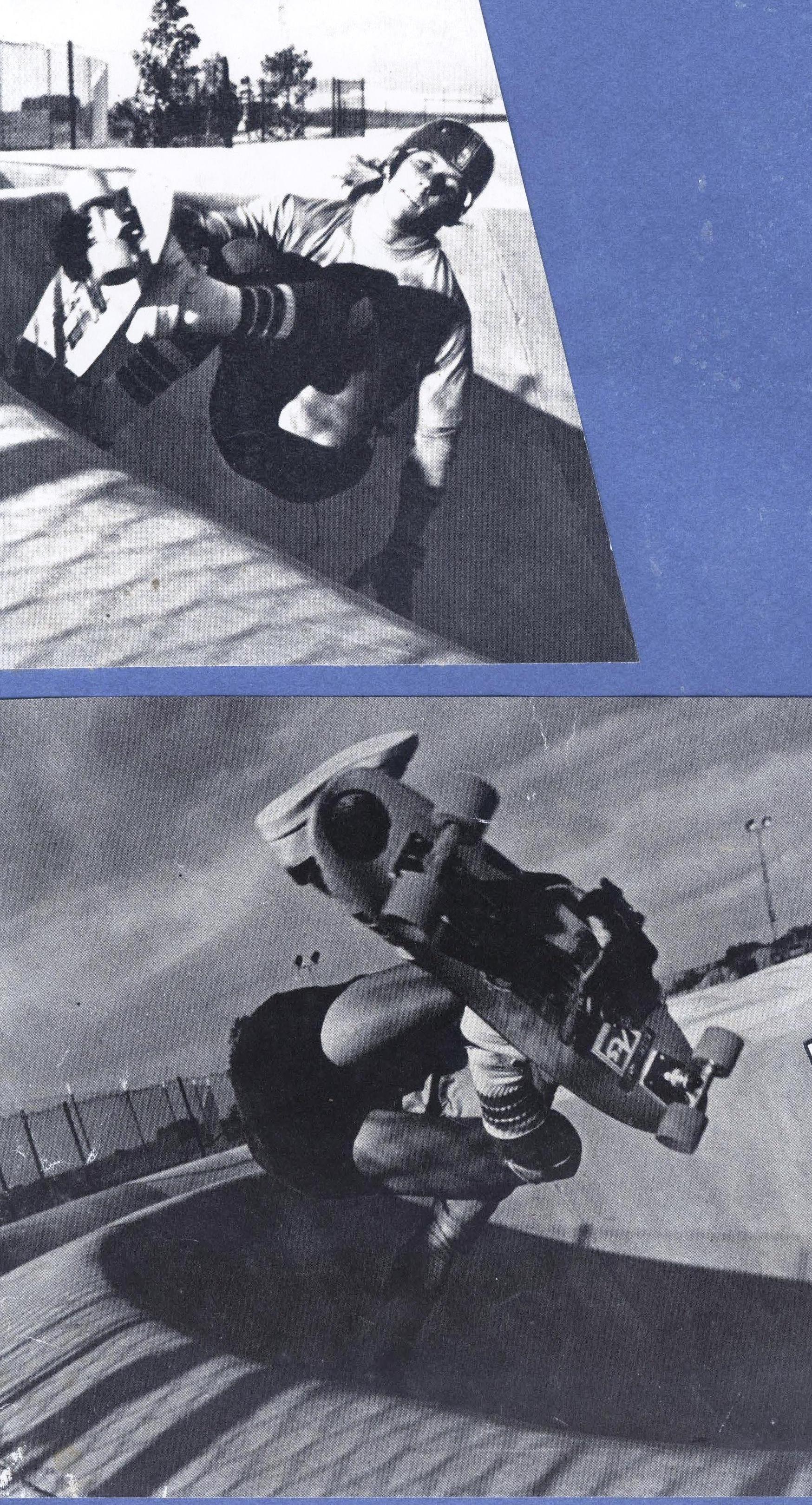

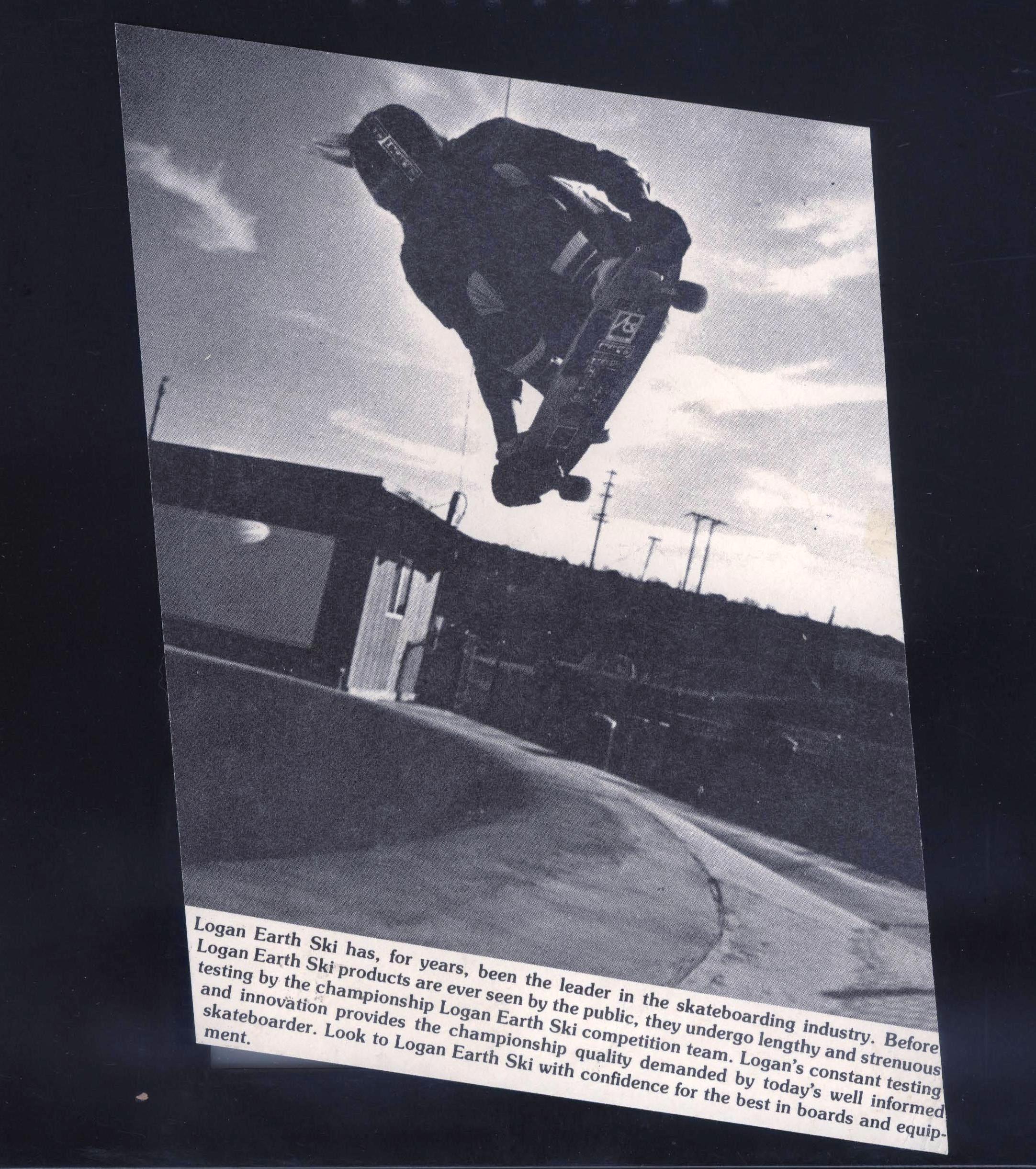

When urethane wheels and grease-packed bearings appeared new things became possible. We gathered in the streets and school playgrounds to practice turns on imaginary waves and we discovered wheelies and spins and tricks that led us into garages to cut new shapes of boards that would help us twist and turn in the California sun. When we were a bit older, we gathered on the wide, black asphalt hills of what would become the resort La Costa, barefoot and with no pads or helmets, testing our equipment and ourselves at forty and even fifty miles an hour. When the extended drought set in during the mid-70s, reservoirs, empty pools and huge concrete drainage pipes offered terrain to match our skills and imaginations. Empty pools at abandoned hotels and forty foot concrete drainage pipes in the desert became the scenes of our young lives. We were a portable culture of athletic kids that would set itself up in any backyard pool we could find. The D-Town boys were, in fact, one of many groups who were defining the contours of modern skateboarding. Much to our surprise—to mine, at least—a genuine sport developed, and a few of us found ourselves sponsored—with equipment, clothing and even small salaries provided by our sponsors. We found ourselves riding fresh concrete in new skate parks, competing against one another, and doing demonstrations for catalogs and magazines.

For whatever reason, I walked away at the peak of it, abandoning the sport just as I had the chance to go on an East Coast exhibition tour. Life moved, and I moved with it, and hence I never found myself in a empty pool or skate park with Kessler. By the time he managed to get the skating park open at Riverside Park at 108th Street in 1995, I was nearing the end of graduate school, completing a doctoral dissertation and teaching writing, poetry and fiction. And while I had spent part of a year living in Manhattan, I missed the opportunity to ride the brick banks under the Brooklyn Bridge, carve a Wall Street handrail or drop into the drained pool in Van Cortlandt Park.

https://ozzieausband.wordpress.com/2014/12/22/it-wont-save-your-life/

You are one of us 🙂 Good to see – Ozzie