The course I described in my last posting, “Writing in an Endangered World,” engaged students with the social movement of environmentalism and new forms of environmental writing. This course was the culmination of many years of scholarly work—both outside and within the classroom—a process I outlined in the inaugural issue of Keene State College’s Arts & Humanities News (Spring 2010). “Writing in an Endangered World,” however, is more than a culmination: it is a starting point for a new project supported by a generous two-year grant I received from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

The grant proposal, approved last month, will support development of an upper-level humanities course in the Integrative Studies Program (ISP). My course will survey changing concepts of nature from the ancient world to the age of Darwin. Students will read a sequence of major texts from the Western tradition alongside religious and scientific documents to understand the broad contours of thinking about the natural world in the Western cultures of Europe, as well as in the Eastern cultures of China and India, and the Arab-World and Africa. Thinking across intellectual traditions will empower students to think comparatively and to understand the dynamics of intertextual and intercultural exchange.

As it is currently envisioned,“What is Nature” will be organized around a sequence of primary texts with supplemental excerpts from treatises, letters, and books of poetry. Students will consider multiple genres of writing, including myth, scientific treatises, and narrative, poetry, in which the question of nature arises, as well as discuss illustrations and diagrams that represent human understandings of the natural world. Readings will include creation stories, including the Maidu Myths, a cycle of tribal creation stories in Western North America; the Hebrew Bible, with emphasis on Genesis and the Psalms; selected hymns from the Indian Brahmanical or Vedic scripture, the Rig Veda, and selections from the Sanskrit verses of Kālidāsa and Dharmakīrti; relevant selections from the Chinese Huai-nan Tzu; Hesiod’s Theogony, and the dialogues of Plato. Students will be introduced to Aristotle’s thinking about the world of nature and read his writing in conjunction with selected dialogues of Plato,specifically the Timaeus and Laws; students will then trace the reception and development of ideas about nature in two narrative poems that influenced thinking about nature through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The first, Lucretius’ De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), an epic poem written in the middle of the first century BC, contrasts the Epicurian view of nature (and man) with the three major Aritstotelian classifications of the physical world; the second, Ovid’s Metamorphosis, describes the creation and history of the world, and its elaborate mythologies express ideas about nature that inspired imaginative writing by such authors as Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton.

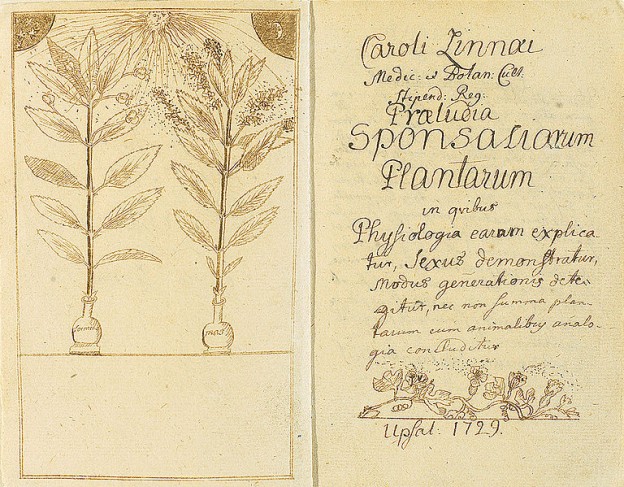

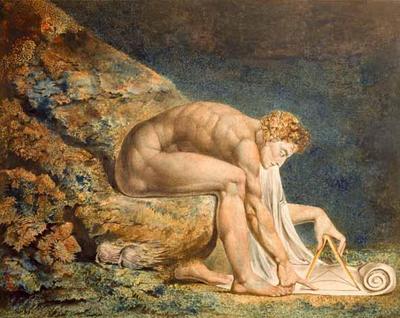

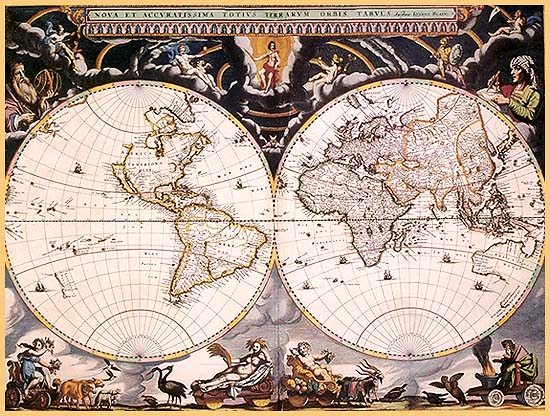

The Roman astronomer Claudius Ptolemy’s argument in the Almagest—that the earth was the center of the universe, and that the sun, planets, and stars revolved around it—will offer students an intellectual context in which to situate the key treatises—and illustrations—that make visible the Copernican system that would replace the Ptolemaic world view. Students will consider sixteenth and seventeenth century views of nature in the writings of Newton, Bacon’s Novum Organum (The New Organon; or, True Directions Concerning the Interpretation of Nature) and Descartes, whose Discourse on Method will help students understand the mechanistic view of nature and method of scientific inquiry. The Enlightenment’s vision of science and the mid-eighteenth century will be represented by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, whose Systema Naturae introduced a classification system that divided living things into two kingdoms (plants and animals), classes, orders, genera, and species, and that led to subsequent ambitions to create a comprehensive taxonomy that would include everything known about the natural world; and the debate about natural degeneracy in the New World in the writings of the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon and Thomas Jefferson.

Americae sive qvartae orbis partis nova et exactissima description, by Diego Gvtiero Philippi (1554-1569), from the Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress

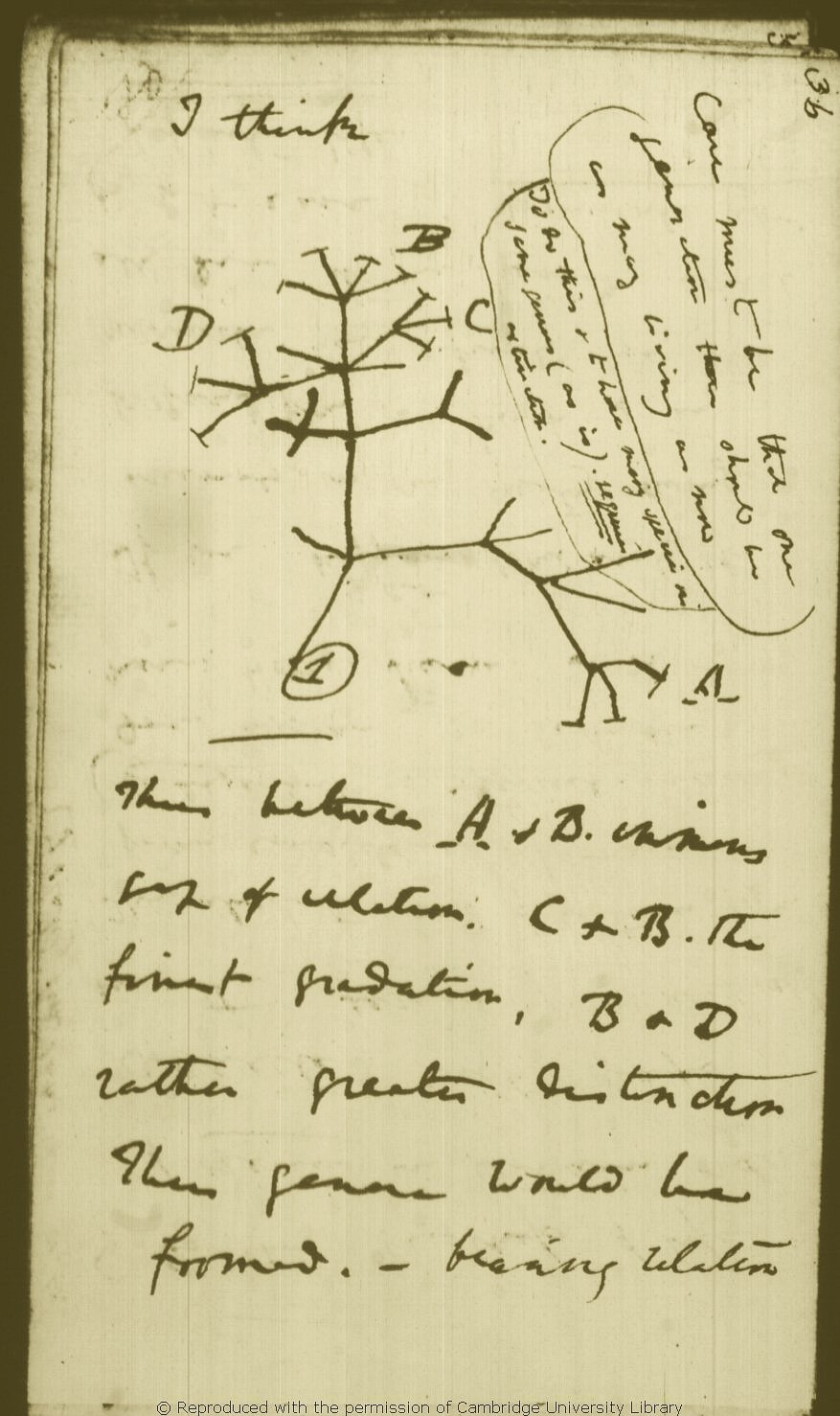

The final unit in the course will be organized around Darwin’s seminal nineteenth century writings. Students will read passages from the narratives in The Voyage of the Beagle (1839), study the argument of his most well-known book On the Origin of Species (1859), and examine his illustrations and journal notes. This segment of the course will introduce students to scientific ideas about nature (and the human) in a broad humanistic framework that will include selections from the German and Romantic poets Frederich Schiller, Frederich Hölderlin, William Blake, William Wordsworth; the natural history writers Gilbert White, William Bartram, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; and the naturalists Alexander von Humboldt and George Perkins Marsh.

The opportunity to develop and teach a pre-disciplinary course with a broad historical scope will extend my ongoing inquiry into experiences and concepts of nature from the perspective of the humanities. It will allow me to return to my doctoral dissertation on theories of inquiry, focused on American intellectual history, that was informed by readings in European literary traditions, philosophy, and the history of science, especially the nineteenth-century writings of the logician and scientist Charles Sanders Peirce, who offers insights into how normal science is practiced, how scientific discoveries come about, and the process that produces paradigm shifts in communities of inquiry that will inform my ways of teaching students how concepts of nature have evolved and changed.

I’m deeply grateful to the National Endowment for supporting this work—work that will begin this summer and continue through the 2011-12 academic year when I will be teaching the course.