“If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite. For. Man has closed himself up, ‘til all he sees is through narrow chinks of his cavern.” –William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

“I like that boy Snyder on Sourdough. He’s a calm son of bitch.” -Blackie Burns

Nearly thirty years ago I drove north from Seattle to the Skagit valley in Washington, with my friend Kevin Craft, for a walk up to the summit of Sourdough Mountain. A series of backcountry tours and climbs with my friend John, a backcountry/climbing range in the national park, had acquainted me with the surrounding peaks and valleys, though the terrain was less familiar to my companion Kevin.

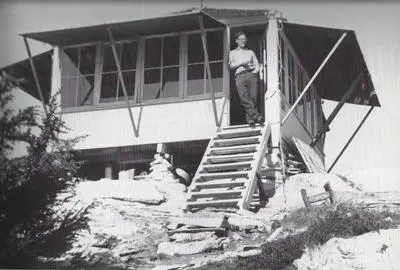

The lookout on Sourdough was built by Glee Davis in 1917. (A peak to the west of Sourdough is named for the Davis family.) The lookout was rebuilt in 1933 and restored in 1998-99. But to get there requires working up a series of broad switchbacks—three-thousand feet in the first three miles—to the four-thousand foot summit.

Kevin happens to be a gifted poet, who has published many poems, books of poems, and has served as the editor of Poetry Northwest. Our late-fall hike went well. And on our walk we both had in mind a poet who had spent time in the North Cascades, Gary Snyder, whose poems are alive with the mountains and valleys of the far West. Here is one:

How Poetry Comes to Me

It comes blundering over the

Boulders at night, it stays

Frightened outside the

Range of my campfire

I go to meet it at the

Edge of the light.

Then, the day following our walk, Kevin sent me a lovely little homage:

How Poetry Comes to Me

After Gary Snyder

Or sometimes I go to meet it

In broad daylight at the lookout

It’s afternoon all morning the light

Slant and subdued running down

The dry creek bed our skin

Sweat-cool stopping to rest the red

Leaves of huckleberry flaring

Like patch fires in the scrub

Going mauve as we pass

The veined skin of their fingers

Now down on all fours

The plump berries clustered there

Not in fear but shriveling

With the season we work through

The dead-end detritus of a sentence

To reach a few ripe words

Like tart and juice at the turn of the trail.

The conversation between these two poems might lead to another poem by Snyder, “Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout,” first published in Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems:

Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies.

I cannot remember things I once read

A few friends, but they are in cities.

Drinking cold snow-water from a tin cup

Looking down for miles

Through high still air.

Snyder spent six weeks at the fire lookout on Sourdough in the summer of 1953—packed in by an old Park Service employee, Blackie Burns. I have been thinking about Snyder since last year when I read Snyder’s Lookout Journals during a week in the archives during a research project. Snyder’s journals are exciting and document a mind on fire—reading William Blake, among others.

Another poet, and close friend of Snyder during their years at Reed College and after, Phillip Whalen, also put in time working as a lookout, and here is his poem “Sourdough Mountain Lookout,” from The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen:

Sourdough Mountain Lookout

Tsung Ping (375—443): “Now I am old and infirm. I fear I shall no more be able to roam among the beautiful mountains. Clarifying my mind, I meditate on the mountain trails and wander about only in dreams.” ––in The Spirit of the Brush, tr. by Shio Sakanishi

for Kenneth Rexroth

I always say I won’t go back to the mountains

I am too old and fat there are bugs mean mules

And pancakes every morning of the world

Mr. Edward Wyman (63)

Steams along the trail ahead of us all

Moaning, “My poor feet ache, my back

Is tired and I’ve got a stiff prick”

Uprooting alder shoots in the rain

Then I’m alone in a glass house on a ridge

Encircled by chiming mountains

With one sun roaring through the house all day

& the others crashing through the glass all night

Conscious even while sleeping

Morning fog in the southern gorge

Gleaming foam restoring the old sea-level

The lakes in two lights green soap and indigo

The high cirque-lake black half-open eye

Ptarmigan hunt for bugs in the snow

Bear peers through the wall at noon

Deer crowd up to see the lamp

A mouse nearly drowns in the honey

I see my bootprints mingle with deer-foot

Bear-paw mule-shoe in the dusty path to the privy

Much later I write down:

“raging. Viking sunrise

The gorgeous death of summer in the east!”

(Influence of a Byronic landscape—

Bent pages exhibiting depravity of style.)

Outside the lookout I lay nude on the granite

Mountain hot September sun but inside my head

Calm dark night with all the other stars

HERACLITUS: “The waking have one common world

But the sleeping turn aside

Each into a world of his own.”

I keep telling myself what I really like

Are music, books, certain land and sea-scapes

The way light falls across them, diffusion of

Light through agate, light itself . . . I suppose

I’m still afraid of the dark

“Remember smart-guy there’s something

Bigger something smarter than you.”

Ireland’s fear of unknown holies drives

My father’s voice (a country neither he

Nor his great-grandfather ever saw)

A sparkly tomb a plated grave

A holy thumb beneath a wave

Everything else they hauled across Atlantic

Scattered and lost in the buffalo plains

Among these trees and mountains

From Duns Scotus to this page

A thousand years

(“. . . a dog walking on this hind legs—

not that he does it well but that he

does it at all.”)

Virtually a blank except for the hypothesis

That there is more to a man

Than the contents of his jock-strap

EMPEDOCLES: “At one time all the limbs

Which are the body’s portion are brought together

By Love in blooming life’s high season; at another

Severed by cruel Strife, they wander each alone

By the breakers of life’s sea.”

Fire and pressure from the sun bear down

Bear down centipede shadow of palm-frond

A limestone lithograph—oysters and clams of stone

Half a black rock bomb displaying brilliant crystals

Fire and pressure Love and Strife bear down

Brontosaurus, look away

My sweat runs down the rock

HERACLITUS: “The transformations of fire

are, first of all, sea; and half of the sea

is earth, half whirlwind. . . .

It scatters and it gathers; it advances

and retires.”

I move out of a sweaty pool

(The sea!)

And sit up higher on the rock

Is anything burning?

The sun itself! Dying

Pooping out, exhausted

Having produced brontosaurus, Heraclitus

This rock, me,

To no purpose

I tell you anyway (as a kind of loving) . . .

Flies & other insects come from miles around

To listen

I also address the rock, the heather,

The alpine fir

BUDDHA: “All the constituents of being are

Transitory: Work out your salvation with diligence.”

(And everything, as one eminent disciple of that master

Pointed out, had been tediously complex ever since.)

There was a bird

Lived in an egg

And by ingenious chemistry

Wrought molecules of albumen

To beak and eye

Gizzard and craw

Feather and claw

My grandmother said:

“Look at them poor bed-

raggled pigeons!”

And the sign in McAlister Street:

“IF YOU CAN’T COME IN

SMILE AS YOU GO BY

LOVE

THE BUTCHER”

I destroy myself, the universe (an egg)

And time—to get an answer:

There are a smiler, a sleeper and a dancer

We repeat the conversation in the glittering dark

Floating beside the sleeper.

The child remarks, “You knew it all the time.”

I: “I keep forgetting that the smiler is

Sleeping; the sleeper, dancing.”

From Sauk Lookout two years before

Some of the view was down the Skagit

To Puget Sound: From above the lower ranges,

Deep in the forest—lighthouses on clear nights.

This year’s rock is a spur from the main range

Cuts the valley in two and is broken

By the river; Ross Dam repairs the break,

Makes trolley buses run

Through the streets of dim Seattle far away.

I’m surrounded by mountains here

A circle of 108 beads, originally seeds

of ficus religiosa

Bo-Tree

A circle, continuous, one odd bead

Larger than the rest and bearing

A tassel (hair-tuft) (the man who sat

under the tree)

In the center of the circle,

a void, an empty figure containing

All that’s multiplied;

Each bead a repetition, a world

Of ignorance and sleep.

Today is the day the goose gets cooked

Day of liberation for the crumbling flower

Knobcone pinecone in the flames

Brandy in the sun

Which, as I said, will disappear

Anyway it’ll be invisible soon

Exchanging places with stars now in my head

To be growing rice in China through the night.

Magnetic storms across the solar plains

Make Aurora Borealis shimmy bright

Beyond the mountains to the north.

Closing the lookout in the morning

Thick ice on the shutters

Coyote almost whistling on a nearby ridge

The mountain is THERE (between two lakes)

I brought back a piece of its rock

Heavy dark-honey color

With a seam of crystal, some of the quartz

Stained by its matrix

Practically indestructible

A shift from opacity to brilliance

(The Zenbos say, “Lightening-flash & flint-spark”)

Like the mountains where it was made

What we see of the world is the mind’s

Invention and the mind

Though stained by it, becoming

Rivers, sun, mule-dung, flies—

Can shift instantly

A dirty bird in a square time

Gone

Gone

REALLY gone

Into the cool

O MAMA!

Like they say, “Four times up,

Three times down.” I’m still on the mountain.

(note: The quotes of Empedocles and Heraclitus are from John Burnet’s Early Greek Philosophy, Meridian Books, New York.)

In his Lookout Journals, Snyder copied out the words from William Blake in the epigraph to this post followed by a single word of commentary: “Ah”