The things which are dear to men at this hour are so on account of the ideas which have emerged on their mental horizon, and which cause the present order of things as a tree bears its apples. A new degree of culture would instantly revolutionize the entire system of human pursuits.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Circles”

In 2013 and 2014 the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) dedicated energy and resources to building a new web site as part of a renewed focus on the digital strategy of the association. We worked from the visionary digital work of Dan Phillipon and built a new web site as part of a more comprehensive digital strategy for the association.

Earlier that year, in my role as president of ASLE, I collaborated with the managing director of our association, Amy McIntryre, on a comprehensive review of our strategic plan. The 2014 Strategic Plan mapped out our continued work as an open and engaged community of scholars in a new mission statement for our association: “The mission of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) is to inspire and promote the work of scholars, educators, students, and writers in the environmental humanities and arts.” Among the revised goals we included outreach through member collaboration and public dialogue; the promotion of equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility; and facilitating the public dissemination of member projects and expertise.

After two years of work I announced in my President’s column the launching of our site and outlined some of the opportunities the new web site would present the members of our association:

In addition to launching the new web site we established a digital strategies committee to guide ASLE’s efforts to facilitate the public dissemination of member projects and expertise. More recently, as a continuing member of the ASLE digital strategies committee, I proposed a working group to explore the possibilities of open education and pedagogy in our ASLE community.

The transformative possibilities of open pedagogy, learning, and resources offer a productive provocation to the members of ASLE as the landscape of higher education continues to change. As public support for higher education continues to ebb we should be reexamining all that we do in our various roles on college and university campuses, in our secondary school classrooms, and our communities of practice. We need to take our advocacy talk for a walk.

One way to do this is to explore open education and pedagogy in our ASLE community. For those less familiar with the emergence of open there are useful definitions in circulation. Open Educational Resources (OERs) are materials shared in the public domain under an intellectual property license that allows their free use and re-purposing by others. These educational resources might include individual and collaborative research, course materials and/or modules, textbooks, videos and media projects, to name a few.

Open pedagogy may align especially well with the mission and values of ASLE. At the same time the values and practices of of open pedagogy-with roots in feminist and critical pedagogies-offer a productive provocation for members of our association whose intellectual work is channeled through narrower disciplinary conversations and artifacts such as monographs that create a buzz but most often in more isolated intellectual hives.

So what might be the connections between academic institutions, open pedagogy and learning, and environmental advocacy? Here are the guiding questions I drafted for the workgroup:

How might members of the Association use open education to move our teaching and research activities into communities outside the academy?

How might ASLE offer undergraduate and graduate students opportunities to create and access OERs as well as promote student agency in intellectual communities within and beyond their home institutions?

How might OERs create new partnerships with nonacademic stakeholders as we continue to work on common challenges and projects in the environmental arts and humanities?

In their recent Message from the Co-Presidents, ASLE members Stacy Alaimo and Jeffrey J. Cohen frame environmental humanism as environmental activism. “We study, write, compose and create because we care about issues like biodiversity, environmental justice, survival in a time of endemic precarity and global catastrophe, and the effects of climate change on humans and nonhumans alike,” they write. Wicked problems such as these do not have easy solutions, of course, though they “have faith that widened community is our best way forward.” This is useful language, I believe, to guide us in where the extraordinary labor of the environmental humanities. But how do we widen the community? How do we work to unsettle the personal and disciplinary and institutional disincentives to intellectual work that widen the community?

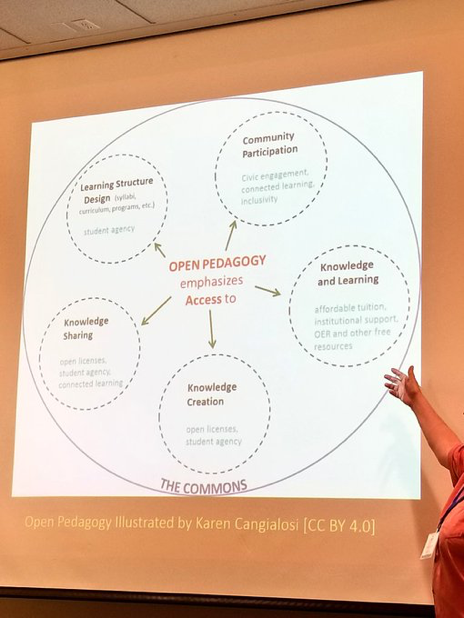

For the past two days I have been at the University of New Hampshire at the annual Academic Technology Institute. During the gathering my friend, biology colleague, and collaborator Karen Cangialosi presented a keynote talk on open education and advocacy.

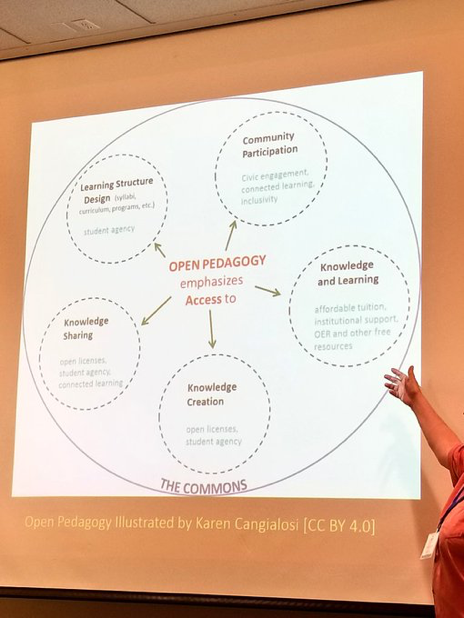

One of Karen’s central claims was that access and agency should be at the core of our work with our students and that the open education movement should refocus academic work on the commons. In the illustration above, Karen emphasizes student agency through course design, knowledge creation, and connected learning, as well as connected learning, community participation, and inclusivity.

One of Karen’s central claims was that access and agency should be at the core of our work with our students and that the open education movement should refocus academic work on the commons. In the illustration above, Karen emphasizes student agency through course design, knowledge creation, and connected learning, as well as connected learning, community participation, and inclusivity.

The use of Open Educational Resources (OER)—and the practices of Open Pedagogy—connects academic labor to the wider public and in turn improves access to education. Teaching and learning in the open is about connecting students to a larger world and to making the process of education more transparent and accessible. With roots in critical pedagogy, open pedagogy values students constructing their own learning process; and, as another colleague writes, practitioners of open pedagogy seek to empower students “while actively critiquing and confronting the industrial and corporate approach of co-opting and packaging ‘teaching technology’ to turn students into consumers.” Instead, teachers and students build ways to leverage the Open web for discovery, creativity and analysis, as well as dialogue with the wider public.

Karen’s advocacy work is part of an ecology of open pedagogy that is to my mind one of the ways ASLE can expand its circle. What are the opportunities for members of ASLE to further its commitments to sharing and contributing knowledge, the public humanities, service learning projects, creating and displaying public art, and engaging our students with local environmental problems? The first answer to that question is gathering the ongoing work that exemplifies the activities already unfolding in what I might call here the ASLE ecology of open.

Open education takes many forms. Below are a few examples of work already happening in ASLE that I hope will expand the scope of our charts: creating OERs; building project sites for education, research, and public engagement; creating course sites on the open web to promote digital identity, fluency, and citizenship.

Creating OERs This can be on OER Commons or OpenStax, by using an open-source publishing platform like Press Books, or engaging with the Rebus Community whose members believe that educational materials for every subject should be a free and open public resource. One example of this kind of work is a resource that my colleague at Plymouth State University created (with her students) The Open Anthology of Early American Literature

Building Project Sites

Ecoarttech is a faculty project site by ASLE members Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint

Play the LA River is a project and collaboration that includes ASLE Member Alison Caruth

The Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies is a project at UCLA

Dawnland Voices features indigenous writing from New England and the Northeast and is edited and curated by ASLE Member Siobhan Senier

Digital Thoreau English professor Paul Schatz’s project at SUNY Geneseo

The Disability History Museum My colleague in the department of history at Keene State College is responsible for developing education curricula and has developed materials with undergraduate students

NICHE: Network in Canadian History & Environment / Nouvelle initiative canadienne en histoire de l’environnement is a Canadian-based confederation of researchers and educators who work at the intersection of nature and history. We explore the historical context of environmental matters and communicate our findings to researchers, policymakers, and the public.

Sustainable Play Brad Rassler’s project for long-form storytelling at the confluence of people, planet, and play.

Petrofictionary is a mode of archiving words and concepts that assist in the study of petrofiction: literary figurations of petroleum, the most important energy source of the twentieth and (so far) twenty-first centuries. The Petrofictionary was created as a collaborative project by the students in English 7087: Petrofictions, at Memorial University of Newfoundland, and edited by Amy Donovan under the guidance of Dr. Fiona Polack. It is intended as an archive, a tool, and a source of both information and inspiration as we consider the wide-reaching implications of petroleum culture and speculate about new modes of human existence after oil.

Domain of One’s Own projects have taken hold at many colleges and universities. The KSCopen.org project, to take one example, emphasizes digital identity, digital fluency and digital citizenship. Some examples of course and project sites at KSCopen.org, including advocacy sites such as NH Science for Citizens, student project sites such as my Far Field Learning Lab

Course Sites

The Open Space of Democracy is an open learning site (as opposed to a course built in a learning management system like Canvas).

Writing in an Endangered World is a course in which student blogs are syndicated to the main site. All of the student writing appears on the course site as well as the individual student sites. The student blogs and the course Project blogs/web sites are listed in the post It’s a Wrap. For example, one student created the Nature In A Quarter Hour Podcast offers a series of reflections (and an interview) based in the field of environmentalism and it’s literary contributions

COPLAC Digital team-taught Distance Learning Seminars with students from more than one institution. For example, I team-taught a course Public Access and the Liberal Arts with a faculty member at Truman State University with students from multiple campuses

Selected Definitions and Resources Karen Cangialosi, has compiled an excellent Open Pedagogy Learning Community Resource List. And most colleges and universities (most often library-based resources) have FAQs about Open Educational Resources (OER). At Keene State College, for example, we have an Open Educational Resources page. The Open Educational Resources page on the Keene State College web site has a useful list of links More About OER.

Open Education Consortium A worldwide community of hundreds of higher education institutions and associated organizations committed to advancing open education.

SPARC: Open Education SPARC believes that Open Educational Resources (OER) maximize the power of the Internet to improve teaching and learning, and increase access to education.

Creative Commons: Education The Education program at Creative Commons works to maximize the benefits of open educational resources (OER) and the return on investment in publicly funded education and research programs.

The Academic Commons Provides serves as a platform/tool that institutions and organizations can use to share their own and learn from each other’s work in an open, collaborative way.”

OER Mythbusting Myths about OER can stop people from using them and causing real educational change. The goal of this publication is to dispel those myths.

Once again, the question of the opportunities: where do we go from here? I will report back with any news as the work of the digital strategies committee takes shape in what I hope will be student and faculty collaborations within, across, and outside our courses, colleges and universities, and communities.