I am becoming increasingly aware of a conversation that I did not know I was a part of. Or perhaps it is that I am finding my way through what I am doing to a conversation. And I am thinking of the “unending conversation” Kenneth Burke describes in his 1941 book The Philosophy of Literary Form:

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress.

The conversation is about teaching and learning. Although the quaint parlor I am asked to imagine is now a stream of thought made possible by digital networks.

After a conversation about openness and education the other day with my friends and colleagues Jenny and Karen, for some reason a book on my shelf caught my eye—a collection of essays by Doug Robinson, A Night on the Ground, A Day in the Open. As it happens, Doug’s writings from the 1970s include “Running the Talus,” an essay that was profoundly inspiring for a young man exploring the valleys and high peaks of California’s Sierra Nevada.

After a conversation about openness and education the other day with my friends and colleagues Jenny and Karen, for some reason a book on my shelf caught my eye—a collection of essays by Doug Robinson, A Night on the Ground, A Day in the Open. As it happens, Doug’s writings from the 1970s include “Running the Talus,” an essay that was profoundly inspiring for a young man exploring the valleys and high peaks of California’s Sierra Nevada.

(Cover art: Lake Basin the High Sierra, Color Woodblock Print, Chiura Obata, 1930)

But Doug’s words bring back more than just adrenaline-fueled days in the mountains before this twenty-something mountaineer headed off to try school—those hundreds of peaks climbed, twenty-pitch days on a granite wall, day-long trans-Sierra runs, high mountain traverses, deep powder days, and backcountry ski descents.

2

In the mid 1990s I became interested in more visible (open?) teaching and learning. Reading a Report published by the Modern Language Association published the year I completed graduate school, making-faculty-work-visible , led to a series of attempts to come to terms with the surprising ways that academic disciplines diminish the value of teaching and pedagogy. I presented three talks on making teaching and learning more visible: in 2001 in New Orleans, “Pedagogy in the Public Domain,” in Chicago, “Open Pedagogy and the Public,” and in New York, “Narratives from the First Year: a Plea for Visibility.”

Looking back, I see myself groping toward an understanding of (and a mild impatience with) teaching as a mostly privatized practice. When I returned from a sabbatical in India, these interests emerged in my scholarship, specifically in an essay I wrote as a guest editor to a special issue of the journal Pedagogy, Centers and Peripheries, and in my teaching, as I began experimenting with opening up my classroom. Inspired by my friend and collaborator Sean Meehan, notably his dynamic teaching blog Comp|Post, I put my course syllabi and materials on the open-source platform Word Press.

As a result, all of the writing in my courses was visible. Everyone—the writer, the teacher, the classmates, and anyone else who might be interested—had access to the intellectual work of a college professor and students in the classroom. Sean also helped me to see a course not only as open, but also as an ongoing project. Each course would frame the core questions and problems that arise in the study of what I was teaching. The course process—the materials, my teaching, student learning, and the writing they produce—would be visible for anyone who might be interested. Students could see what their peers were doing. And the materials the students were producing would persist.

I began teaching differently in the open as well. I found myself writing on the course blog before class sessions, preparing myself for my time with students, thinking aloud and modeling for students forms of thinking and writing I want them to do. Following class sessions, I was writing as well—reflecting on the intellectual work of the students, making new connections, and openly processing my way to the next class session.

This pedagogical emphasis on process—and on sustaining thought so that students have the time to struggle through the process of formulating and developing their thinking—led me to us more sustained intellectual projects that allow students to experiment with writing conventions while developing (and claiming) their emerging voice. Students were reading books in my classes, as always—the real books that need to be read and that I was trained to teach. But students were also reading on web-based portals, repositories, and archives. My students were making use of web-based resources, from writing guides and handbooks to digital archives, such as Calisphere, the Walt Whitman Archive, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), NICHE: Network in Canadian History & Environment / Nouvelle initiative canadienne en histoire de l’environnement.

3

I drove down the Freeway

And turned off at an exit

And went along a highway

Til it came to a sideroad

Drove up the sideroad

Til it turned to a dirt road

Full of bumps, and stopped.

Walked up a trail

But the trail got rough

And it faded away—

Out in the open,

Everywhere to go.

—Gary Snyder, from Left Out in the Rain

In 2010 I wrote Professors, Students, Blogs that described my use of blogs for teaching. In addition to Sean, I was inspired by a former colleague who keeps one of the most consistently interesting blogs on planet earth, Hoarded Ordinaries. Lorianne inspired me to use a blog in the way I am right now: making visible my intellectual work professing at a public liberal arts college.

And I was learning from my students. One day a graduate student stopped by my office to ask whether she might not write an essay in my American poetry class. She wanted to create a hypertext reading of a poem called “Piute Creek.” This was fifteen years ago and I did not really know what she was proposing. But without hesitation I said yes. What she made was powerful. Her work has stayed with me, though the site was built on a server that is no longer there. Another of my students, working on an individualized major in Writing in Biology, made a blog called Creative Biology. And a student doing an independent study called “The Ecology of the New England Garden” captured some of what she was doing on the blog Regional Roots.

And I was learning from my students. One day a graduate student stopped by my office to ask whether she might not write an essay in my American poetry class. She wanted to create a hypertext reading of a poem called “Piute Creek.” This was fifteen years ago and I did not really know what she was proposing. But without hesitation I said yes. What she made was powerful. Her work has stayed with me, though the site was built on a server that is no longer there. Another of my students, working on an individualized major in Writing in Biology, made a blog called Creative Biology. And a student doing an independent study called “The Ecology of the New England Garden” captured some of what she was doing on the blog Regional Roots.

In the spring of 2013 I wrote a blog post called Digital Compost to make visible some of the emergent technologies and their uses in literary and cultural studies. More and more, I was directing students to digital archives and repositories to access primary documents. I was sharing what was rapidly becoming available with my students who are studying at a public college that had not been able to provide access to these kinds of materials.

More and more I am spending my days in the open. My writing course Searching for Wildness was the first course that I designed to persist as an ongoing intellectual project. The course is organized around texts, questions, ideas, and histories, as all good humanities courses are. But the course is open and active. Each group of students who signs up for the class is contributing to an ongoing cultural project of understanding and making meaning.

More and more I am spending my days in the open. My writing course Searching for Wildness was the first course that I designed to persist as an ongoing intellectual project. The course is organized around texts, questions, ideas, and histories, as all good humanities courses are. But the course is open and active. Each group of students who signs up for the class is contributing to an ongoing cultural project of understanding and making meaning.

Out in the open. Everywhere to go.

4

This past spring I designed and taught an interdisciplinary American Studies course on the natural and cultural history of California. California Dreaming focused on the natural and cultural history of California. I asked students to explore a simple question that becomes more and more interesting as you think with it: What explains California?

I borrowed the question from the journalist Phillip L. Fradkin’s book The Seven States of California: A Natural and Human History. Each student was asked to design and implement a project on the natural and cultural history of California. They were asked, first, to connect their own interests to materials in archives and on the web. Second, they organized their primary materials into that would help to explain California. They wrote essays, created Word Press, Tumblr, Wix, or other web-based sites to describe the primary materials they had gathered as a body of work–describing the objects and artifacts, making connections, and telling a story that expands and deepens our understanding of the natural and /or cultural history of California.

The students explored California through places and bioregions, individual histories and collective narratives of identity and culture, ideals, and representations. Students explored the historical myth and material reality of the Golden State through indigenous cultures and narratives of exploration; waves of immigration and demographic change; the presence of racism and multicultural history and identity; water, orange groves, and agribusiness; cities and suburbia; political corruption and capital crimes; money and Hollywood moguls; technological booms and busts; film, fiction, and fashion; popular music and poetry; sex, drugs, rock and roll; narratives of self-actualization and alienation; the emergence of surfing and skateboarding; skiing, mountaineering, and rock climbing; television, sports, and celebrity culture.

The students explored California through places and bioregions, individual histories and collective narratives of identity and culture, ideals, and representations. Students explored the historical myth and material reality of the Golden State through indigenous cultures and narratives of exploration; waves of immigration and demographic change; the presence of racism and multicultural history and identity; water, orange groves, and agribusiness; cities and suburbia; political corruption and capital crimes; money and Hollywood moguls; technological booms and busts; film, fiction, and fashion; popular music and poetry; sex, drugs, rock and roll; narratives of self-actualization and alienation; the emergence of surfing and skateboarding; skiing, mountaineering, and rock climbing; television, sports, and celebrity culture.

Their research projects—their answers to the question, “What is California?”—offers evidence of the generative intellectual work that is possible in the open, even in a first-year college course.

5

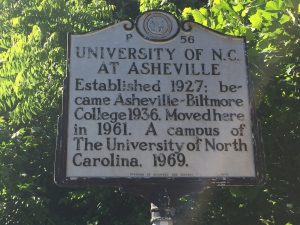

This summer I spent a week in Asheville, North Carolina at a course development workshop in preparation for co-teaching a multi-campus, team-taught, distance seminar in digital scholarship with professor of English Cole Woodcox from Truman State University.

Public Access and the Liberal Arts: A Narrative History, or NAPLA, is funded by the Council of Public Liberal Arts (COPLAC), with support from the Executive Director of COPLAC, William Spellman. The course idea emerged a year earlier in a COPLAC Digital Humanities Workshop at the University of Mary Washington that brought together faculty from Keene State College, Sonoma State, University of Montevallo, USC Aiken, Midwestern State, and Truman State to design distance-learning, digital humanities courses.

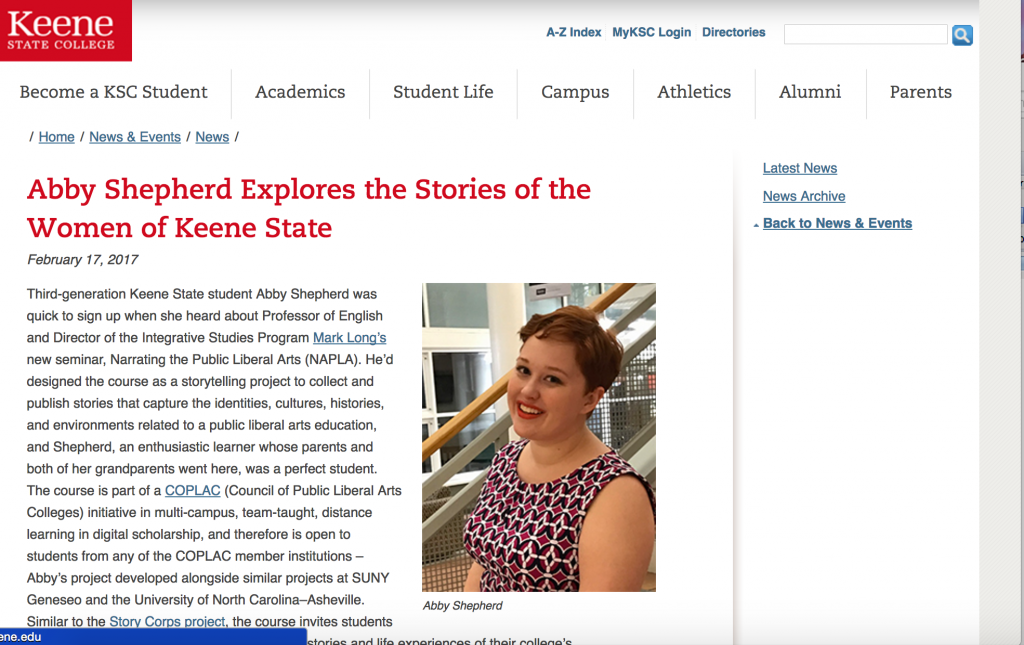

Our digital humanities project is documenting the emergence of the public liberal arts. Similar to the Story Corps project started in 2003, the course is about digital storytelling and the narratives of selected COPLAC institutions. Students are capturing the stories and life experiences of students, alumni, staff and faculty, and constructing a digital resource that captures the history and the prospects of the public liberal arts. As designers and editors of the digital archives, students are deepening their own sense of place in higher education and making visible the history of the liberal arts at the institution in which they are studying.

Our digital humanities project is documenting the emergence of the public liberal arts. Similar to the Story Corps project started in 2003, the course is about digital storytelling and the narratives of selected COPLAC institutions. Students are capturing the stories and life experiences of students, alumni, staff and faculty, and constructing a digital resource that captures the history and the prospects of the public liberal arts. As designers and editors of the digital archives, students are deepening their own sense of place in higher education and making visible the history of the liberal arts at the institution in which they are studying.

Our primary course objective is for teams enrolled at COPLAC campuses to research and represent the histories of their local campus. The context for this research will be the 1944 G.I. Bill and public access to higher education and, later, increased public access to liberal arts education. The objectives of the course are to 1) build an online archive of oral histories by alumni, faculty, staff and current students; 2) use digital tools to produce a layered, web-based narrative that includes audio and video stories, images, maps and documentary evidence of their home campus and 3) collaborate with faculty mentors to integrate their web site projects with a main COPLAC site to make visible the story of the public liberal arts. Our vision for this public storytelling project is to offer a digital resource for current students, alumni, educators, administrators, development and admission offices, historians, archivists, and the public in general.

Our primary course objective is for teams enrolled at COPLAC campuses to research and represent the histories of their local campus. The context for this research will be the 1944 G.I. Bill and public access to higher education and, later, increased public access to liberal arts education. The objectives of the course are to 1) build an online archive of oral histories by alumni, faculty, staff and current students; 2) use digital tools to produce a layered, web-based narrative that includes audio and video stories, images, maps and documentary evidence of their home campus and 3) collaborate with faculty mentors to integrate their web site projects with a main COPLAC site to make visible the story of the public liberal arts. Our vision for this public storytelling project is to offer a digital resource for current students, alumni, educators, administrators, development and admission offices, historians, archivists, and the public in general.

Interested in knowing more? Visit the NAPLA Course Site to check in on the action. I’ll also be sharing more here as we get further along in the course.